It is late. I am beat. I found a poem that sort of captures my mood tonight.

Saint Marty is ready for a drink and a long nap.

The Coming of Light

by: Mark Strand

Even this late it happens:

the coming of love, the coming of light.

You wake and the candles are lit as if by themselves,

stars gather, dreams pour into your pillows,

sending up warm bouquets of air.

Even this late the bones of the body shine

and tomorrow's dust flares into breath.

Poet...Musician...Thinker...Blogger...Teacher...Husband...Father...I'm not perfect, but I try!

Friday, March 31, 2017

March 31: Like Heaven, All I Do Is Work, Mindless Fun

A man in a boxcar across the way called out through the ventilator that a man had just died in there. So it goes. There were four guards who heard him. They weren't excited by the news.

"Yo, yo," said one, nodding dreamily. "Yo, yo."

And the guard didn't open the car with the dead man on it. They opened the next car instead, and Billy Pilgrim was enchanted by what was in there. It was like heaven. There was candlelight, and there were bunks with quilts and blankets heaped on them. There was a cannonball stove with a steaming coffeepot on top. There was a table with a bottle of wine and a loaf of bread and a sausage on it. There were four bowls of soup.

After his long march, Billy gets a little glimpse of heaven. Warm bunks. A candlelit table with bread and wine and sausage and coffee. It is a scene in direct contrast to the boxcars stuffed with prisoners of war, coughing and groaning and dying.

I am sitting on my couch at about 9:30 at night, and it feels like heaven to me. It is the first time I've really had to relax all day. When I got off work (over eight hours answering phones), I threw myself into cleaning at my parents' house. Another hour or so of work. I am beat. Nearly falling asleep.

In about an hour, I have to pick up my daughter from a friend's house. And then I will be able to go to bed. Tomorrow is going to be another long day. My son has another wrestling tournament, and we have to get an early start. Seven-thirty in the morning. Right now, that does not sound very appealing to me.

It seems, sometimes, that all I do is work. At the medical office. At the university. At home. It never seems to end. The only time I really sit down is when I'm too tired to do anything else. Like now. Next week, I will be taking a couple days off. Friday and Monday. We will be traveling to the Wisconsin Dells for a dance competition. I am hoping for a few hours of mindless fun there.

Again, I'm not complaining. Work is a blessing, too. I just wish I wasn't blessed with so much of it.

Saint Marty is thankful tonight for a comfortable couch that fits his ass well.

"Yo, yo," said one, nodding dreamily. "Yo, yo."

And the guard didn't open the car with the dead man on it. They opened the next car instead, and Billy Pilgrim was enchanted by what was in there. It was like heaven. There was candlelight, and there were bunks with quilts and blankets heaped on them. There was a cannonball stove with a steaming coffeepot on top. There was a table with a bottle of wine and a loaf of bread and a sausage on it. There were four bowls of soup.

After his long march, Billy gets a little glimpse of heaven. Warm bunks. A candlelit table with bread and wine and sausage and coffee. It is a scene in direct contrast to the boxcars stuffed with prisoners of war, coughing and groaning and dying.

I am sitting on my couch at about 9:30 at night, and it feels like heaven to me. It is the first time I've really had to relax all day. When I got off work (over eight hours answering phones), I threw myself into cleaning at my parents' house. Another hour or so of work. I am beat. Nearly falling asleep.

In about an hour, I have to pick up my daughter from a friend's house. And then I will be able to go to bed. Tomorrow is going to be another long day. My son has another wrestling tournament, and we have to get an early start. Seven-thirty in the morning. Right now, that does not sound very appealing to me.

It seems, sometimes, that all I do is work. At the medical office. At the university. At home. It never seems to end. The only time I really sit down is when I'm too tired to do anything else. Like now. Next week, I will be taking a couple days off. Friday and Monday. We will be traveling to the Wisconsin Dells for a dance competition. I am hoping for a few hours of mindless fun there.

Again, I'm not complaining. Work is a blessing, too. I just wish I wasn't blessed with so much of it.

Saint Marty is thankful tonight for a comfortable couch that fits his ass well.

Thursday, March 30, 2017

March 30: Book Club Meeting, Mark Strand, "From the Long Sad Party"

Just finished our Book Club meeting. We read Pot Farm by my friend, Matt Gavin Frank. Matt joined us for pizza and chicken wings and brownies. We talked about marijuana and family and diamond smuggling and the Mormon religion. Oh, and we talked about his book. He was such fun.

I don't have much more to add. I will return to Slaughterhouse tomorrow night. Too tired right now for deep thoughts.

Saint Marty is thankful that he did not have a long, sad party this evening.

From the Long Sad Party

by: Mark Strand

Someone was saying

something about shadows covering the field, about

how things pass, how one sleeps towards morning

and the morning goes.

Someone was saying

how the wind dies down but comes back,

how shells are the coffins of wind

but the weather continues.

It was a long night

and someone said something about the moon shedding its

white

on the cold field, that there was nothing ahead

but more of the same.

Someone mentioned

a city she had been in before the war, a room with two

candles

against a wall, someone dancing, someone watching.

We began to believe

the night would not end.

Someone was saying the music was over and no one had

noticed.

Then someone said something about the planets, about the

stars,

how small they were, how far away.

I don't have much more to add. I will return to Slaughterhouse tomorrow night. Too tired right now for deep thoughts.

Saint Marty is thankful that he did not have a long, sad party this evening.

From the Long Sad Party

by: Mark Strand

Someone was saying

something about shadows covering the field, about

how things pass, how one sleeps towards morning

and the morning goes.

Someone was saying

how the wind dies down but comes back,

how shells are the coffins of wind

but the weather continues.

It was a long night

and someone said something about the moon shedding its

white

on the cold field, that there was nothing ahead

but more of the same.

Someone mentioned

a city she had been in before the war, a room with two

candles

against a wall, someone dancing, someone watching.

We began to believe

the night would not end.

Someone was saying the music was over and no one had

noticed.

Then someone said something about the planets, about the

stars,

how small they were, how far away.

Wednesday, March 29, 2017

March 29: Friend's House, Mark Strand, "For Jessica, My Daughter"

I am hoping to watch a few episodes of American Horror Story: Hotel with my daughter tonight. It is Spring Break, and she hasn't been home in the evening very much. She's been over at a friend's house, hanging out. Not a boyfriend's house. Just a friend.

Sometimes, I'm amazed that I had a part in creating my daughter. She's smart and funny and beautiful and talented and graceful. She's been talking about studying to be an anesthesiologist when she gets to college. I looked at her this afternoon, felt my heart sort of unfold.

Saint Marty hopes that he's been a good father.

For Jessica, My Daughter

by: Mark Strand

Tonight I walked,

lost in my own meditation,

and was afraid,

not of the labyrinth

that I have made of love and self

but of the dark and faraway.

I walked, hearing the wind in the trees,

feeling the cold against my skin,

but what I dwelled on

were the stars blazing

in the immense arc of sky.

Jessica, it is so much easier

to think of our lives,

as we move under the brief luster of leaves,

loving what we have,

than to think of how it is

such small beings as we

travel in the dark

with no visible way

or end in sight.

Yet there were times I remember

under the same sky

when the body's bones became light

and the wound of the skull

opened to receive

the cold rays of the cosmos,

and were, for an instant,

themselves the cosmos,

there were times when I could believe

we were the children of stars

and our words were made of the same

dust that flames in space,

times when I could feel in the lightness of breath

the weight of a whole day

come to rest.

But tonight

it is different.

Afraid of the dark

in which we drift or vanish altogether,

I imagine a light

that would not let us stray too far apart,

a secret moon or mirror,

a sheet of paper,

something you could carry

in the dark

when I am away.

Sometimes, I'm amazed that I had a part in creating my daughter. She's smart and funny and beautiful and talented and graceful. She's been talking about studying to be an anesthesiologist when she gets to college. I looked at her this afternoon, felt my heart sort of unfold.

Saint Marty hopes that he's been a good father.

For Jessica, My Daughter

by: Mark Strand

Tonight I walked,

lost in my own meditation,

and was afraid,

not of the labyrinth

that I have made of love and self

but of the dark and faraway.

I walked, hearing the wind in the trees,

feeling the cold against my skin,

but what I dwelled on

were the stars blazing

in the immense arc of sky.

Jessica, it is so much easier

to think of our lives,

as we move under the brief luster of leaves,

loving what we have,

than to think of how it is

such small beings as we

travel in the dark

with no visible way

or end in sight.

Yet there were times I remember

under the same sky

when the body's bones became light

and the wound of the skull

opened to receive

the cold rays of the cosmos,

and were, for an instant,

themselves the cosmos,

there were times when I could believe

we were the children of stars

and our words were made of the same

dust that flames in space,

times when I could feel in the lightness of breath

the weight of a whole day

come to rest.

But tonight

it is different.

Afraid of the dark

in which we drift or vanish altogether,

I imagine a light

that would not let us stray too far apart,

a secret moon or mirror,

a sheet of paper,

something you could carry

in the dark

when I am away.

March 29: Worse Places, Chicken Pot Pie, Better Off

Billy Pilgrim was packed into a boxcar with many other privates. He and Roland Weary were separated. Weary was packed into another car in the same train.

There were narrow ventilators at the corners of the car, under the eaves. Billy stood by one of these, and, as the crowd pressed against him, he climbed part way up a diagonal corner brace to make more room. This placed his eyes on a level with the ventilator, so he could see another train about ten yards away.

Germans were writing on the cars with blue chalk--the number of persons in each car, their rank, their nationality, the date on which they had been put aboard. Other Germans were securing the hasps on the car doors with wire and spikes and other trackside trash. Billy could hear somebody writing on his car, too, but he couldn't see who was doing it.

Most of the privates on Billy's car were very young--at the end of childhood. But crammed into the corner with Billy was a former hobo who was forty years old.

"I been hungrier than this," the hobo told Billy. "I been in worse places than this. This ain't so bad."

I really love the hobo in this passage. Jammed into a boxcar with a dozens of other people, probably starved for days, exhausted from marching and marching, the hobo still isn't feeling too bad. Think about it. It's better to be a prisoner of war than a homeless person in the United States. That says quite a bit. In the wealthiest country of the world, there are hobos dying of hunger and exposure.

I am not going to get all political here. I'm not going to focus on the poor and working poor. People who work two, sometimes three jobs and still can't pay their bills or feed their kids. Minimum wage that doesn't even provide a minimum living. Kids that only get hot meals at school. Senior citizens who can't afford their medications.

Nope, I'm not going to talk about any of that.

I'm going to talk about chicken pot pie, which I had for dinner tonight. It was delicious, with crispy crust and chunks of meat, potatoes, and peas. I had two pieces, and it made me feel warm and satisfied. I'm thankful that I had a warm meal tonight. I'm better off than a good portion of the world's population.

Sometimes, it's easy to forget how lucky I am. A loving wife. Two great kids. A house. A car that works. A couple decent jobs where I am relatively respected. Books to read. A laptop computer to write blog posts on. A warm bed to sleep in.

As the hobo tells Billy Pilgrim, this ain't so bad.

Saint Marty is thankful for chicken pot pie and his kids and wife and books and laptop tonight.

There were narrow ventilators at the corners of the car, under the eaves. Billy stood by one of these, and, as the crowd pressed against him, he climbed part way up a diagonal corner brace to make more room. This placed his eyes on a level with the ventilator, so he could see another train about ten yards away.

Germans were writing on the cars with blue chalk--the number of persons in each car, their rank, their nationality, the date on which they had been put aboard. Other Germans were securing the hasps on the car doors with wire and spikes and other trackside trash. Billy could hear somebody writing on his car, too, but he couldn't see who was doing it.

Most of the privates on Billy's car were very young--at the end of childhood. But crammed into the corner with Billy was a former hobo who was forty years old.

"I been hungrier than this," the hobo told Billy. "I been in worse places than this. This ain't so bad."

I really love the hobo in this passage. Jammed into a boxcar with a dozens of other people, probably starved for days, exhausted from marching and marching, the hobo still isn't feeling too bad. Think about it. It's better to be a prisoner of war than a homeless person in the United States. That says quite a bit. In the wealthiest country of the world, there are hobos dying of hunger and exposure.

I am not going to get all political here. I'm not going to focus on the poor and working poor. People who work two, sometimes three jobs and still can't pay their bills or feed their kids. Minimum wage that doesn't even provide a minimum living. Kids that only get hot meals at school. Senior citizens who can't afford their medications.

Nope, I'm not going to talk about any of that.

I'm going to talk about chicken pot pie, which I had for dinner tonight. It was delicious, with crispy crust and chunks of meat, potatoes, and peas. I had two pieces, and it made me feel warm and satisfied. I'm thankful that I had a warm meal tonight. I'm better off than a good portion of the world's population.

Sometimes, it's easy to forget how lucky I am. A loving wife. Two great kids. A house. A car that works. A couple decent jobs where I am relatively respected. Books to read. A laptop computer to write blog posts on. A warm bed to sleep in.

As the hobo tells Billy Pilgrim, this ain't so bad.

Saint Marty is thankful for chicken pot pie and his kids and wife and books and laptop tonight.

Tuesday, March 28, 2017

March 28: Lost Keys, Mark Strand, "The Garden"

I have lost my keys. Well, actually, I have misplaced my keys. They are not in my normal coat pocket. They are not in my house or my car. Therefore, I believe that I have left them on my desk at work. At least, that is what I'm hoping.

My wife sometimes calls me the absent-minded professor. I have a habit of losing things temporarily. I get distracted, walk off, forget. When I was a child, I was highly unfocused. I bounced from reading to writing to wanting to digging up a dinosaur in the backyard to finding a dirty magazine under my brother's mattress.

That may sound like ADHD. I have never been diagnosed. My mother's solution for my erratic attention was making me take piano lessons. It worked. I was able to practice for extended periods of time at the keyboard. And that ability to concentrate spilled over into other areas of my life.

However, I still get distracted, still misplace things.

Poetry helps Saint Marty focus, as well.

The Garden

by: Mark Strand

It shines in the garden,

My wife sometimes calls me the absent-minded professor. I have a habit of losing things temporarily. I get distracted, walk off, forget. When I was a child, I was highly unfocused. I bounced from reading to writing to wanting to digging up a dinosaur in the backyard to finding a dirty magazine under my brother's mattress.

That may sound like ADHD. I have never been diagnosed. My mother's solution for my erratic attention was making me take piano lessons. It worked. I was able to practice for extended periods of time at the keyboard. And that ability to concentrate spilled over into other areas of my life.

However, I still get distracted, still misplace things.

Poetry helps Saint Marty focus, as well.

The Garden

by: Mark Strand

for Robert Penn Warren

It shines in the garden,

in the white foliage of the chestnut tree,

in the brim of my father’s hat

as he walks on the gravel.

In the garden suspended in time

my mother sits in a redwood chair:

light fills the sky,

the folds of her dress,

the roses tangled beside her.

And when my father bends

to whisper in her ear,

when they rise to leave

and the swallows dart

and the moon and stars

have drifted off together, it shines.

Even as you lean over this page,

late and alone, it shines: even now

in the moment before it disappears.March 28: Wild Bob, Poetic Equations, Dickinson's Advice

There was another long silence, with the colonel dying and dying, drowning where he stood. And then he dried out wetly, "It's me, boys! It's Wild Bob!" That is what he had always wanted his troops to call him: "Wild Bob."

None of the people who could hear him were actually from his regiment, except for Roland Weary, and Weary wasn't listening. All Weary could think of was the agony in his own feet.

But the colonel imagined that he was addressing his beloved troops for the last time, and he told them that they had nothing to be ashamed of, that there were dead Germans all over the battlefield who wished to God that they had never heard of the Four-fifty-first. He said that after the war he was going to have a regimental reunion in his home town, which was Cody, Wyoming. He was going to barbecue whole steers.

He said all the while staring into Billy's eyes. He made the inside of poor Billy's skull echo with balderdash. "God be with you, boys!: he said, and that echoed and echoed. And then he said, "If you're ever in Cody, Wyoming, just ask for Wild Bob!"

I was there. So was my old war buddy, Bernard V. O'Hare.

This passage is a strange combination of fiction and fact. Billy Pilgrim is there. Roland Weary is there. Wild Bob is there. And so is Vonnegut and his war buddy, Bernard. That means that at least part of this passage is fact. Wild Bob probably was at this railroad yard, calling out, "God be with you boys!" Vonnegut heard him, decided to put him in his book about the war.

In anything I write, there is always a measure of truth. Poetry is all about getting to the heart of an experience. I have written poems about diabetes and adultery, mental illness and spiritual crisis. There's an inclination for readers of poetry to automatically assume that a poem is 100% true. The equations in most people's heads go something like this:

Speaker in Poem = Poet

Therefore, if

Speaker in Poem is cutting himself

then

Poet is a cutter

All of those statements may be true. The poet may be writing from personal experience. Or, the poet's wife may be a cutter. Or daughter. Or son. Or sister. There is real truth, and there is poetic truth. Walt Whitman probably did take the Brooklyn ferry home from Manhattan, but he may not have. Robert Frost may have stopped by some woods on a winter night, or he may not have. Dickinson probably heard a fly buzz at some point in her life.

It's all a matter of taking real experience (a ferry ride, an insect on a windowsill, a horse-drawn sleigh ride) and transforming it into universal experience. That's the poet's job. At least, that's my job as a poet. I want to my readers to recognize themselves. So, I guess that I would prefer the poetic equations to go something like this:

Speaker in Poem = Reader of Poem

Therefore, if

Speaker in Poem is cutting himself

then

Reader of Poem understands the experience of cutting

So, if I write a poem about having an alcoholic father, that doesn't mean my father is or was an alcoholic. Likewise, if I write a poem about seeing my father beat my mother, that doesn't mean that I was raised in a house filled with domestic violence. I am telling all the truth, but I am following Emily Dickinson's advice: I am telling it slant. Just like Kurt Vonnegut.

Saint Marty is thankful tonight for the truth of a warm late March evening.

None of the people who could hear him were actually from his regiment, except for Roland Weary, and Weary wasn't listening. All Weary could think of was the agony in his own feet.

But the colonel imagined that he was addressing his beloved troops for the last time, and he told them that they had nothing to be ashamed of, that there were dead Germans all over the battlefield who wished to God that they had never heard of the Four-fifty-first. He said that after the war he was going to have a regimental reunion in his home town, which was Cody, Wyoming. He was going to barbecue whole steers.

He said all the while staring into Billy's eyes. He made the inside of poor Billy's skull echo with balderdash. "God be with you, boys!: he said, and that echoed and echoed. And then he said, "If you're ever in Cody, Wyoming, just ask for Wild Bob!"

I was there. So was my old war buddy, Bernard V. O'Hare.

This passage is a strange combination of fiction and fact. Billy Pilgrim is there. Roland Weary is there. Wild Bob is there. And so is Vonnegut and his war buddy, Bernard. That means that at least part of this passage is fact. Wild Bob probably was at this railroad yard, calling out, "God be with you boys!" Vonnegut heard him, decided to put him in his book about the war.

In anything I write, there is always a measure of truth. Poetry is all about getting to the heart of an experience. I have written poems about diabetes and adultery, mental illness and spiritual crisis. There's an inclination for readers of poetry to automatically assume that a poem is 100% true. The equations in most people's heads go something like this:

Speaker in Poem = Poet

Therefore, if

Speaker in Poem is cutting himself

then

Poet is a cutter

All of those statements may be true. The poet may be writing from personal experience. Or, the poet's wife may be a cutter. Or daughter. Or son. Or sister. There is real truth, and there is poetic truth. Walt Whitman probably did take the Brooklyn ferry home from Manhattan, but he may not have. Robert Frost may have stopped by some woods on a winter night, or he may not have. Dickinson probably heard a fly buzz at some point in her life.

It's all a matter of taking real experience (a ferry ride, an insect on a windowsill, a horse-drawn sleigh ride) and transforming it into universal experience. That's the poet's job. At least, that's my job as a poet. I want to my readers to recognize themselves. So, I guess that I would prefer the poetic equations to go something like this:

Speaker in Poem = Reader of Poem

Therefore, if

Speaker in Poem is cutting himself

then

Reader of Poem understands the experience of cutting

So, if I write a poem about having an alcoholic father, that doesn't mean my father is or was an alcoholic. Likewise, if I write a poem about seeing my father beat my mother, that doesn't mean that I was raised in a house filled with domestic violence. I am telling all the truth, but I am following Emily Dickinson's advice: I am telling it slant. Just like Kurt Vonnegut.

Saint Marty is thankful tonight for the truth of a warm late March evening.

Monday, March 27, 2017

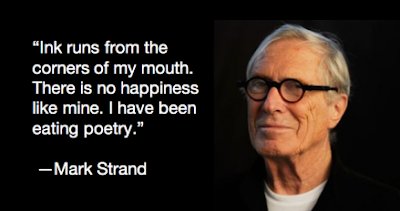

March 27: Laureate Without a Plan, Poet of the Week, Mark Strand, "Eating Poetry"

Mark Strand was named U. S. Poet Laureate in 1990, and, like Ted Kooser from last week, I've forgotten how much I love Mark Strand's work. So, he is the Poet of the Week.

Ever since being named Poet Laureate of the U. P., I've felt like I should be doing something poetic every day. Standing on a street corner, reading Walt Whitman. Picking random names out of the phone book and sending out postcards with poems on them. I have scheduled a few readings and a year-long poetry workshop series, but I'm still finding my footing.

Saint Marty is a laureate without a plan right now.

Eating Poetry

by: Mark Strand

Ever since being named Poet Laureate of the U. P., I've felt like I should be doing something poetic every day. Standing on a street corner, reading Walt Whitman. Picking random names out of the phone book and sending out postcards with poems on them. I have scheduled a few readings and a year-long poetry workshop series, but I'm still finding my footing.

Saint Marty is a laureate without a plan right now.

Eating Poetry

by: Mark Strand

Ink runs from the corners of my mouth.

There is no happiness like mine.

I have been eating poetry.

The librarian does not believe what she sees.

Her eyes are sad

and she walks with her hands in her dress.

The poems are gone.

The light is dim.

The dogs are on the basement stairs and coming up.

Their eyeballs roll,

their blond legs burn like brush.

The poor librarian begins to stamp her feet and weep.

She does not understand.

When I get on my knees and lick her hand,

she screams.

I am a new man.

I snarl at her and bark.

I romp with joy in the bookish dark.March 28: Coughed and Coughed, Stranger in a Strange Land, Same Worries

The Germans sorted out the prisoners according to rank. They put sergeants with sergeants, majors with majors, and so on. A squad of full colonels was halted near Billy. One of them had double pneumonia. He had a high fever and vertigo. As the railroad yard dipped and swooped around the colonel, he tried to hold himself steady by staring into Billy's eyes.

The colonel coughed and coughed, and then he said to Billy, "You one of my boys?" This was a man who had lost an entire regiment, about forty-five hundred men--a lot of them children, actually. Billy didn't reply. The question made no sense.

"What was your outfit?" said the colonel. He coughed and coughed. Every time he inhaled his lungs rattled like greasy paper bags.

Billy couldn't remember the outfit he was from.

"You from the Four-fifty-first?"

"Four-fifty-first what?" said Billy.

There was a silence. "Infantry regiment," said the colonel at last.

"Oh," said Billy Pilgrim.

Billy really is a stranger in a strange land. He was never prepared to be in combat, and he certainly isn't prepared to be a prisoner of war. He was an aide to a chaplain. I don't think he ever expected to see a German soldier, let alone be captured by some. Billy literally doesn't know how to respond to the colonel's questions.

I have been feeling a little stranger-in-a-strange-land myself today. Woke up feeling incredibly sad for some reason. That mood followed me for most of the morning. I simply couldn't shake it. I went to bed last night worrying about bills. Woke up with the same worries. Walked around for about six hours, wondering where my life had gone wrong. Can't pay bills. Can't afford vacations. Didn't even have enough money to buy something caffeinated to drag me out of the doldrums this a.m.

It is now about five o'clock in the afternoon, and my mood has shifted somewhat. I have a class to teach in about an hour, but most of it will be spent watching and discussing Michael Moore's documentary Sicko. An easy night. Perhaps that is what has buoyed my spirits. Plus I really like these students a lot. They make teaching writing for three hours on a Monday night almost fun.

So, I am not quite so melancholy now. Just had dinner. Delicious. Might have an Oatmeal Cream Pie for dessert. Delicious again. And then, Michael Moore railing against America's health care system. Great fun.

Saint Marty is thankful for the food he ate tonight. Amen.

The colonel coughed and coughed, and then he said to Billy, "You one of my boys?" This was a man who had lost an entire regiment, about forty-five hundred men--a lot of them children, actually. Billy didn't reply. The question made no sense.

"What was your outfit?" said the colonel. He coughed and coughed. Every time he inhaled his lungs rattled like greasy paper bags.

Billy couldn't remember the outfit he was from.

"You from the Four-fifty-first?"

"Four-fifty-first what?" said Billy.

There was a silence. "Infantry regiment," said the colonel at last.

"Oh," said Billy Pilgrim.

Billy really is a stranger in a strange land. He was never prepared to be in combat, and he certainly isn't prepared to be a prisoner of war. He was an aide to a chaplain. I don't think he ever expected to see a German soldier, let alone be captured by some. Billy literally doesn't know how to respond to the colonel's questions.

I have been feeling a little stranger-in-a-strange-land myself today. Woke up feeling incredibly sad for some reason. That mood followed me for most of the morning. I simply couldn't shake it. I went to bed last night worrying about bills. Woke up with the same worries. Walked around for about six hours, wondering where my life had gone wrong. Can't pay bills. Can't afford vacations. Didn't even have enough money to buy something caffeinated to drag me out of the doldrums this a.m.

It is now about five o'clock in the afternoon, and my mood has shifted somewhat. I have a class to teach in about an hour, but most of it will be spent watching and discussing Michael Moore's documentary Sicko. An easy night. Perhaps that is what has buoyed my spirits. Plus I really like these students a lot. They make teaching writing for three hours on a Monday night almost fun.

So, I am not quite so melancholy now. Just had dinner. Delicious. Might have an Oatmeal Cream Pie for dessert. Delicious again. And then, Michael Moore railing against America's health care system. Great fun.

Saint Marty is thankful for the food he ate tonight. Amen.

Sunday, March 26, 2017

March 26: Spring Break, Classic Saint Marty, "Empire of the Ants"

Getting tired now. My kids are on Spring Break this week. Bedtimes will be pushed back. No alarm clocks will be set. Mornings will be mid-mornings. Homework will be set aside until next Sunday night. I remember those glorious days of freedom when I was a kid.

I, on the other hand, have been correcting and grading all weekend. Tomorrow, I will rise at my normal time, stumble through the dark to the bathroom, and start my day as usual. A bowl of Honey Nut Cheerios. A few minutes of the morning news. Then, out the door to face the icy world.

Last year, it was Easter weekend. I was getting dressed for church. Setting out some carrots for the Easter Bunny. Anticipating the lights of the Easter Vigil:

March 26, 2016: Easter Vigil Mass, Flickering Candles, Billy Collins, "Catholicism"

I owe my disciples a few Billy Collins poems. I will offer no excuses for neglecting the former Poet Laureate of the United States. But, I intend to make up for my negligence today.

Of course, Billy Collins is Irish American, so he has all of the Catholic trappings that I have in my background, as well. The poem I have chosen to share with you is about guilt and redemption (in a way). Totally appropriate for Holy Saturday.

Tonight, I will be playing the pipe organ and singing at the Easter Vigil Mass at my church. Lots of darkness and candles and fire and incense. Two hours of celebration. This may not sound like a fun way to spend a Saturday night, but the Easter Vigil is the most beautiful worship service of the year. It causes me great stress--I have three pages of Gregorian chant to sing. But there is something about seeing the church filled with the night and then slowly filling with flickering candles that moves me deeply.

Saint Marty is ready for the light.

Catholicism

by: Billy Collins

There's a possum who appears here at odd times,

often walking up the path to the house

in the middle of the day like a little ghost

with a long tail and a blank expression on his face.

He likes to slip behind the woodpile,

but sometimes he gets so close to the window

where I am standing with a glass in my hand

that I start to review my sins, systematically

going from one commandment to the next.

What is it about him that causes me

to begin an examination of conscience,

calling to mind my failings in this time of reflection?

It could just be the twitching of the tail

and that white face, but his slow priestly pace

also makes a contribution, as do the tiny paws,

more like hands, really, with opposable thumbs

able to carry a nut or dig a hole in the earth

of lift a chalice above his head

or even deliver a document,

I am thinking as he nears the back door,

not merely a subpoena but an order

of excommunication with my name and a date

written in fine Italian ink

and signed with a flourish of the papal sash.

And a poem from another Poet Laureate, this one not quite so famous or rich or talented:

I, on the other hand, have been correcting and grading all weekend. Tomorrow, I will rise at my normal time, stumble through the dark to the bathroom, and start my day as usual. A bowl of Honey Nut Cheerios. A few minutes of the morning news. Then, out the door to face the icy world.

Last year, it was Easter weekend. I was getting dressed for church. Setting out some carrots for the Easter Bunny. Anticipating the lights of the Easter Vigil:

March 26, 2016: Easter Vigil Mass, Flickering Candles, Billy Collins, "Catholicism"

I owe my disciples a few Billy Collins poems. I will offer no excuses for neglecting the former Poet Laureate of the United States. But, I intend to make up for my negligence today.

Of course, Billy Collins is Irish American, so he has all of the Catholic trappings that I have in my background, as well. The poem I have chosen to share with you is about guilt and redemption (in a way). Totally appropriate for Holy Saturday.

Tonight, I will be playing the pipe organ and singing at the Easter Vigil Mass at my church. Lots of darkness and candles and fire and incense. Two hours of celebration. This may not sound like a fun way to spend a Saturday night, but the Easter Vigil is the most beautiful worship service of the year. It causes me great stress--I have three pages of Gregorian chant to sing. But there is something about seeing the church filled with the night and then slowly filling with flickering candles that moves me deeply.

Saint Marty is ready for the light.

Catholicism

by: Billy Collins

There's a possum who appears here at odd times,

often walking up the path to the house

in the middle of the day like a little ghost

with a long tail and a blank expression on his face.

He likes to slip behind the woodpile,

but sometimes he gets so close to the window

where I am standing with a glass in my hand

that I start to review my sins, systematically

going from one commandment to the next.

What is it about him that causes me

to begin an examination of conscience,

calling to mind my failings in this time of reflection?

It could just be the twitching of the tail

and that white face, but his slow priestly pace

also makes a contribution, as do the tiny paws,

more like hands, really, with opposable thumbs

able to carry a nut or dig a hole in the earth

of lift a chalice above his head

or even deliver a document,

I am thinking as he nears the back door,

not merely a subpoena but an order

of excommunication with my name and a date

written in fine Italian ink

and signed with a flourish of the papal sash.

And a poem from another Poet Laureate, this one not quite so famous or rich or talented:

Empire of the Ants

by: Martin Achatz

I remember the film vaguely:

Joan Collins battled an army

Of mutated ants, big as African

Rhinos, things still driven by insectile

Instinct to gather food, store it

For cold months, for a ravenous

Queen and her blind larvae.

Ants swarmed schools, houses, boats,

Like Greeks laying siege to Troy.

They carried off victims to tunnels,

Chambers of sand and decay,

Moved fast, in a perpetual state

Of urgency, because they somehow

Knew it was only a matter of time

Before Collins and her crew

Invented a magnifying glass

Big enough to fry thorax, antenna,

Wreak Armageddon, restore

The planet to its proper, human

Balance. This

summer, ants overrun

My house. From a

June and July

Filled with heat, drought, they find

Sanctuary in my cool kitchen,

The dust of sugar on counter,

Peach residue on bowl and rag.

In the mornings, I flip on lights,

Watch ants scatter like shadows

Across sink, floor, garbage can.

I press my thumb on stragglers,

Feel them curl, burst under

My pressure. Most

retreat until

Darkness returns, until they sense

Safety, like a crumb of brownie,

A core of apple, calling them out.

The way toxic waste called the mutants.

The way the horse called Trojans.

The way sirens called Ulysses,

Made the rocks soft, inviting,

Sweet as Penelope’s thighs.

Saturday, March 25, 2017

March 25: Simpler Times, Ted Kooser, "A Room in the Past"

A quick poem this morning about the past. I have been feeling nostalgia for simpler times, an easier life, when people cared about each other. Watched out for each other. When I felt safe and happy all the time. You know, when President Obama was in the White House.

Saint Marty wishes everybody a happy, grace-filled day.

A Room in the Past

by: Ted Kooser

Saint Marty wishes everybody a happy, grace-filled day.

A Room in the Past

by: Ted Kooser

It’s a kitchen. Its curtains fill

with a morning light so bright

you can’t see beyond its windows

into the afternoon. A kitchen

falling through time with its things

in their places, the dishes jingling

up in the cupboard, the bucket

of drinking water rippled as if

a truck had just gone past, but that truck

was thirty years. No one’s at home

in this room. Its counter is wiped,

and the dishrag hangs from its nail,

a dry leaf. In housedresses of mist,

blue aprons of rain, my grandmother

moved through this life like a ghost,

and when she had finished her years,

she put them all back in their places

and wiped out the sink, turning her back

on the rest of us, forever. March 25: Bearskin Coats, Human Disasters, Turning a Blind Eye

A motion-picture camera was set up at the border--to record the fabulous victory. Two civilians in bearskin coats were leaning on the camera when Billy and Weary came by. They had run out of film hours ago.

One of them singled out Billy's face for a moment, then focused at infinity again. There was a tiny plume of smoke at infinity. There was a battle there. People were dying there. So it goes.

And the sun went down, and Billy found himself bobbing in place in a railroad yard. There were rows and rows of boxcars waiting. They had brought reserves to the font. Now they were going to take prisoners into Germany's interior.

Flashlight beams danced crazily.

The scene Vonnegut describes certainly calls to mind images of the Holocaust. A railroad yard. Boxcars waiting to be loaded with people. A plume of smoke in the sky. These details are loaded with meaning. Billy and Roland are about to be loaded onto one of these trains.

The world hasn't learned its lesson from the Holocaust. There have been genocides in Rwanda, Bosnia, Cambodia. And, as before, people looked in the other direction. It's so easy simply to ignore, rather than take notice. Because to take notice means that you have to take action.

Right now, there seems to be a whole lot of people willing to ignore, and it's a little frightening. There are human disasters taking place in Syria, and yet the citizens of this planet are unwilling to step up and do something about it. Instead of compassion and charity, refugees are met with suspicion and hatred. I live in a country where that is happening. Over seventy years ago, the United States turned away Jewish refugees from Germany. History seems to be repeating itself.

Hopefully, the tide is going to turn. I find the tidal wave of nationalism that seems to be sweeping across the world more than a little alarming. My sister has Down Syndrome. When she was young, my mother had to fight over and over simply to get her into a classroom, provide her with an education. The comment she frequently got from school teachers, administrators, and other parents was, "We have to take care of our kids before we take care of yours."

There is not "our" and "yours" in society. Nobody is isolated. We need to take care of each other. Turning a blind eye on a person in need is not a tenet of any world religion.

Saint Marty is thankful today for the compassionate, loving people in his life.

One of them singled out Billy's face for a moment, then focused at infinity again. There was a tiny plume of smoke at infinity. There was a battle there. People were dying there. So it goes.

And the sun went down, and Billy found himself bobbing in place in a railroad yard. There were rows and rows of boxcars waiting. They had brought reserves to the font. Now they were going to take prisoners into Germany's interior.

Flashlight beams danced crazily.

The scene Vonnegut describes certainly calls to mind images of the Holocaust. A railroad yard. Boxcars waiting to be loaded with people. A plume of smoke in the sky. These details are loaded with meaning. Billy and Roland are about to be loaded onto one of these trains.

The world hasn't learned its lesson from the Holocaust. There have been genocides in Rwanda, Bosnia, Cambodia. And, as before, people looked in the other direction. It's so easy simply to ignore, rather than take notice. Because to take notice means that you have to take action.

Right now, there seems to be a whole lot of people willing to ignore, and it's a little frightening. There are human disasters taking place in Syria, and yet the citizens of this planet are unwilling to step up and do something about it. Instead of compassion and charity, refugees are met with suspicion and hatred. I live in a country where that is happening. Over seventy years ago, the United States turned away Jewish refugees from Germany. History seems to be repeating itself.

Hopefully, the tide is going to turn. I find the tidal wave of nationalism that seems to be sweeping across the world more than a little alarming. My sister has Down Syndrome. When she was young, my mother had to fight over and over simply to get her into a classroom, provide her with an education. The comment she frequently got from school teachers, administrators, and other parents was, "We have to take care of our kids before we take care of yours."

There is not "our" and "yours" in society. Nobody is isolated. We need to take care of each other. Turning a blind eye on a person in need is not a tenet of any world religion.

Saint Marty is thankful today for the compassionate, loving people in his life.

Friday, March 24, 2017

March 24: Oncology Office, Ted Kooser, "At the Cancer Clinic"

On Fridays, I work around the corner from an oncology clinic. On my breaks, I walk past the office to sit by some windows at the end of the hallway. Its waiting room is always full.

This afternoon, as I was passing the door, a woman came out of the office. She was wearing a head scarf and looked pretty tired. I smiled at her and said, "Good afternoon." Her face immediately lit up. She smiled at me and said, "Happy Friday!"

I stopped and smiled back. "You have a great weekend," I said.

She laughed. "Every day is a great day."

I nodded at her. "Yes," I said, "I guess you're right."

She smiled again and turned toward the elevator.

Saint Marty met God today. Her head scarf was beautiful.

At the Cancer Clinic

by: Ted Kooser

She is being helped toward the open door

that leads to the examining rooms

by two young women I take to be her sisters.

Each bends to the weight of an arm

and steps with the straight, tough bearing

of courage. At what must seem to be

a great distance, a nurse holds the door,

smiling and calling encouragement.

How patient she is in the crisp white sails

of her clothes. The sick woman

peers from under her funny knit cap

to watch each foot swing scuffing forward

and take its turn under her weight.

There is no restlessness or impatience

or anger anywhere in sight. Grace

fills the clean mold of this moment

and all the shuffling magazines grow still.

This afternoon, as I was passing the door, a woman came out of the office. She was wearing a head scarf and looked pretty tired. I smiled at her and said, "Good afternoon." Her face immediately lit up. She smiled at me and said, "Happy Friday!"

I stopped and smiled back. "You have a great weekend," I said.

She laughed. "Every day is a great day."

I nodded at her. "Yes," I said, "I guess you're right."

She smiled again and turned toward the elevator.

Saint Marty met God today. Her head scarf was beautiful.

At the Cancer Clinic

by: Ted Kooser

She is being helped toward the open door

that leads to the examining rooms

by two young women I take to be her sisters.

Each bends to the weight of an arm

and steps with the straight, tough bearing

of courage. At what must seem to be

a great distance, a nurse holds the door,

smiling and calling encouragement.

How patient she is in the crisp white sails

of her clothes. The sick woman

peers from under her funny knit cap

to watch each foot swing scuffing forward

and take its turn under her weight.

There is no restlessness or impatience

or anger anywhere in sight. Grace

fills the clean mold of this moment

and all the shuffling magazines grow still.

March 24: Dragon's Teeth, Revising a Poem, Glaringly Obvious

Billy found the afternoon stingingly exciting. There was so much to see--dragon's teeth, killing machines, corpses with bare feet that were blue and ivory. So it goes.

Bobbing up-and-down, up-and-down, Billy beamed lovingly at a bright lavender farmhouse that had been spattered with machine-gun bullets. Standing in its cockeyed doorway was a German colonel. With him was his unpainted whore.

Billy crashed into Weary's shoulder, and Weary cried out sobbingly. "Walk right! Walk right!"

They were climbing a gentle rise now. When they reached the top, they weren't in Luxembourg any more. They were in Germany.

Billy still on his way to Dresden. All around him, reminders of war. Corpses. Tanks. Guns. Building riddled with bullet holes. German officers. And, of course, the other P.O.W.s, marching along, terrified and in pain. Sounds like the typical day of a contingent college professor to me.

It has been a long week, and I'm glad it has come to an end. I don't have much planned for the next couple of days, except grading. Lots of grading. If I'm lucky, I'll work on revising a poem from my new manuscript. Well, actually, the manuscript is a few years old. I just took it out the other day, reread it. The experience was, at turns, painful and wonderful. It's glaringly obvious which poems need work.

My goal, by the end of the weekend, is to have at least two of the poems revised. That will leave 44 to go. I am determined, by the beginning of June, to have a book to send out to publishers. It will be a difficult process, sort of like marching to Germany in clogs. But, really, writing is rewriting, and that's my task.

So, tonight, Saint Marty is grateful for a red pen.

Bobbing up-and-down, up-and-down, Billy beamed lovingly at a bright lavender farmhouse that had been spattered with machine-gun bullets. Standing in its cockeyed doorway was a German colonel. With him was his unpainted whore.

Billy crashed into Weary's shoulder, and Weary cried out sobbingly. "Walk right! Walk right!"

They were climbing a gentle rise now. When they reached the top, they weren't in Luxembourg any more. They were in Germany.

Billy still on his way to Dresden. All around him, reminders of war. Corpses. Tanks. Guns. Building riddled with bullet holes. German officers. And, of course, the other P.O.W.s, marching along, terrified and in pain. Sounds like the typical day of a contingent college professor to me.

It has been a long week, and I'm glad it has come to an end. I don't have much planned for the next couple of days, except grading. Lots of grading. If I'm lucky, I'll work on revising a poem from my new manuscript. Well, actually, the manuscript is a few years old. I just took it out the other day, reread it. The experience was, at turns, painful and wonderful. It's glaringly obvious which poems need work.

My goal, by the end of the weekend, is to have at least two of the poems revised. That will leave 44 to go. I am determined, by the beginning of June, to have a book to send out to publishers. It will be a difficult process, sort of like marching to Germany in clogs. But, really, writing is rewriting, and that's my task.

So, tonight, Saint Marty is grateful for a red pen.

Thursday, March 23, 2017

March 23: Picture of Me, Ted Kooser, "Abandoned Farmhouse"

I often wonder what people will think of me when I'm gone. I wonder what readers think when they stumble across a stray blog post I've written. What kind of picture of me do they assemble in their minds.

What I hope they see is a man who loves his wife and children. A hard-working husband and father. A person of faith. Someone who can laugh at himself. Good poet and writer, hopefully. Generous. Compassionate. Friendly. And hung like a horse.

That's Saint Marty.

Abandoned Farmhouse

by: Ted Kooser

He was a big man, says the size of his shoes

on a pile of broken dishes by the house;

a tall man too, says the length of the bed

in an upstairs room; and a good, God-fearing man,

says the Bible with a broken back

on the floor below the window, dusty with sun;

but not a man for farming, say the fields

cluttered with boulders and the leaky barn.

A woman lived with him, says the bedroom wall

papered with lilacs and the kitchen shelves

covered with oilcloth, and they had a child,

says the sandbox made from a tractor tire.

Money was scarce, say the jars of plum preserves

and canned tomatoes sealed in the cellar hole.

And the winters cold, say the rags in the window frames.

It was lonely here, says the narrow country road.

Something went wrong, says the empty house

in the weed-choked yard. Stones in the fields

say he was not a farmer; the still-sealed jars

in the cellar say she left in a nervous haste.

And the child? Its toys are strewn in the yard

like branches after a storm—a rubber cow,

a rusty tractor with a broken plow,

a doll in overalls. Something went wrong, they say.

What I hope they see is a man who loves his wife and children. A hard-working husband and father. A person of faith. Someone who can laugh at himself. Good poet and writer, hopefully. Generous. Compassionate. Friendly. And hung like a horse.

That's Saint Marty.

Abandoned Farmhouse

by: Ted Kooser

He was a big man, says the size of his shoes

on a pile of broken dishes by the house;

a tall man too, says the length of the bed

in an upstairs room; and a good, God-fearing man,

says the Bible with a broken back

on the floor below the window, dusty with sun;

but not a man for farming, say the fields

cluttered with boulders and the leaky barn.

A woman lived with him, says the bedroom wall

papered with lilacs and the kitchen shelves

covered with oilcloth, and they had a child,

says the sandbox made from a tractor tire.

Money was scarce, say the jars of plum preserves

and canned tomatoes sealed in the cellar hole.

And the winters cold, say the rags in the window frames.

It was lonely here, says the narrow country road.

Something went wrong, says the empty house

in the weed-choked yard. Stones in the fields

say he was not a farmer; the still-sealed jars

in the cellar say she left in a nervous haste.

And the child? Its toys are strewn in the yard

like branches after a storm—a rubber cow,

a rusty tractor with a broken plow,

a doll in overalls. Something went wrong, they say.

March 23: Snot and Blutwurst, Share of Disappointments, Humility

Billy and his group joined the river of humiliation, and the late afternoon sun came out from the clouds. The Americans didn't have the road to themselves. The westbound lane boiled and boomed with vehicles which were rushing German reserves to the front. The reserves were violent, windburned, bristly men. They had teeth like piano keys.

They were festooned with machine-gun belts, smoked cigars and guzzled booze. They took wolfish bites from sausages, patted their horny palms with potato-masher grenades.

One soldier in black was having a drunk hero's picnic all by himself on top of a tank. He spit on the Americans. The spit hit Roland Weary's shoulder, gave Weary a fourragere of snot and blutwurst and tobacco juice and Schnapps.

This passage is about humiliation. Billy marches with other American P.O.W.s, and the Germans do not treat them as guests. Roland is marching in clogs that turn his feet into hamburger, and the soldiers eat and drink in front of their prisoners, become intoxicated. One German solider hawks a wad of snot and spit on Roland, and Roland is forced to wear it like a badge of dishonor.

I have to say that I have never experienced this kind of humiliation, inflicted on me by another person. Except maybe in high school gym class. I've had my share of disappointments, for sure. One of the most difficult times of my life was when my wife and I were separated. I found it very hard telling friends and coworkers about the situation. I carried around a whole bundle of emotions, and shame was one of the key ingredients in that bundle. I couldn't speak about it without crying. So I tried not to speak about it.

I'm not telling you this so you'll feel sorry for me. I came to really dislike the looks of pity that flashed across people's faces when they saw me. They were momentary and well-intentioned expressions of sympathy, but, for some reason, they made me angry. I didn't feel brave. Didn't want anyone to feel sorry for me. I was too busy feeling sorry for myself.

I was raising my five-year-old daughter by myself, working two full-time jobs, volunteering in my daughter's kindergarten class. I planned birthday parties, bought Halloween costumes, attended parent-teacher conferences. I did everything that I was supposed to do, and I even managed to have some moments of genuine happiness. However, after my daughter fell asleep, I would do laundry, pack lunches, and generally wallow in a kind of grief mixed with humiliation. I felt like a failure.

Everything turned out for the best. My wife and I reconciled. She got her addiction under control after many years. We had another child. It hasn't been smooth sailing all the time. We still struggle (with money, especially), and that struggle comes with a certain amount of humility. Not humiliation. For the most part, though, we have a really good life.

Tonight, Saint Marty is thankful for his struggles. They make him appreciate his blessings even more.

They were festooned with machine-gun belts, smoked cigars and guzzled booze. They took wolfish bites from sausages, patted their horny palms with potato-masher grenades.

One soldier in black was having a drunk hero's picnic all by himself on top of a tank. He spit on the Americans. The spit hit Roland Weary's shoulder, gave Weary a fourragere of snot and blutwurst and tobacco juice and Schnapps.

This passage is about humiliation. Billy marches with other American P.O.W.s, and the Germans do not treat them as guests. Roland is marching in clogs that turn his feet into hamburger, and the soldiers eat and drink in front of their prisoners, become intoxicated. One German solider hawks a wad of snot and spit on Roland, and Roland is forced to wear it like a badge of dishonor.

I have to say that I have never experienced this kind of humiliation, inflicted on me by another person. Except maybe in high school gym class. I've had my share of disappointments, for sure. One of the most difficult times of my life was when my wife and I were separated. I found it very hard telling friends and coworkers about the situation. I carried around a whole bundle of emotions, and shame was one of the key ingredients in that bundle. I couldn't speak about it without crying. So I tried not to speak about it.

I'm not telling you this so you'll feel sorry for me. I came to really dislike the looks of pity that flashed across people's faces when they saw me. They were momentary and well-intentioned expressions of sympathy, but, for some reason, they made me angry. I didn't feel brave. Didn't want anyone to feel sorry for me. I was too busy feeling sorry for myself.

I was raising my five-year-old daughter by myself, working two full-time jobs, volunteering in my daughter's kindergarten class. I planned birthday parties, bought Halloween costumes, attended parent-teacher conferences. I did everything that I was supposed to do, and I even managed to have some moments of genuine happiness. However, after my daughter fell asleep, I would do laundry, pack lunches, and generally wallow in a kind of grief mixed with humiliation. I felt like a failure.

Everything turned out for the best. My wife and I reconciled. She got her addiction under control after many years. We had another child. It hasn't been smooth sailing all the time. We still struggle (with money, especially), and that struggle comes with a certain amount of humility. Not humiliation. For the most part, though, we have a really good life.

Tonight, Saint Marty is thankful for his struggles. They make him appreciate his blessings even more.

Wednesday, March 22, 2017

March 22: Poetry Reading, Ted Kooser, "Look for Me"

I am going to a reading tonight. Really looking forward to it. It will consist of people sharing poems about Upper Peninsula wetlands. There are going to be some really good writers there. This time, I just get to sit back and relax. Enjoy the words.

Looking for a Ted Kooser poem tonight, I was again reminded of what a great poet he is. He takes something simple, everyday, and makes it into a miracle.

Saint Marty wants to be Ted Kooser when he grows up.

Look for Me

by: Ted Kooser

Looking for a Ted Kooser poem tonight, I was again reminded of what a great poet he is. He takes something simple, everyday, and makes it into a miracle.

Saint Marty wants to be Ted Kooser when he grows up.

Look for Me

by: Ted Kooser

Look for me under the hood

of that old Chevrolet settled in weeds

at the end of the pasture.

I'm the radiator that spent its years

bolted in front of an engine

shoving me forward into the wind.

Whatever was in me in those days

has mostly leaked away,

but my cap's still screwed on tight

and I know the names of all these

tattered moths and broken grasshoppers

the rest of you've forgotten.March 22: Smiles forThem All, Life of the Office, My Natural State

Ever since Billy had been thrown into shrubbery for the sake of a picture, he had been seeing Saint Elmo's fire, a sort of electronic radiance around the heads of his companions and captors. It was in the treetops and on the rooftops of Luxembourg, too. It was beautiful.

Billy was marching with his hands on top of his head, and so were all the other Americans. Billy was bobbing up-and-down, up-and-down. Now he crashed into Roland Weary accidentally. "I beg your pardon," he said.

Weary's eyes were tearful, too. Weary was crying because of horrible pains in his feet. The hinged clogs were transforming his feet into blood puddings.

At each road intersection Billy's group was joined by more Americans with their hands on top of their haloed heads. Billy had smiles for them all. They were moving like water, downhill all the time, and they flowed at last to a main highway on a valley's floor. Through the valley flowed a Mississippi of humiliated Americans. Tens of thousands of Americans shuffled eastward, their hands clasped on top of their heads. They sighed and groaned.

What amazes me about this passage is that Billy Pilgrim is smiling the whole time. He's marching for miles and miles with his hands clasped on top of his head. When he bumps into Roland, he politely excuses himself, as if he's in the ticket line for a movie. And when he sees new people, Billy greets them with more smiles. I almost expect him to call out, "Welcome aboard!"

Perhaps Billy's smile is a byproduct of his time hopping. He has a larger vision. He knows what the past, present, and future hold. Or maybe it's just Billy's natural disposition. He's a friendly guy. For the most part, I'm known for being a pretty positive person, too. At work, I'm the life of the office. Always joking and laughing. Just the other day, a coworker said to me, "Can you just be here all the time? You make me so happy."

My good mood is a conscious choice. I have to work at it. If you've been reading this blog for any length of time, you already know that I have a penchant for dark moods and reflections. I am not a happy person most of the time. I worry. Fret. Brood. Dwell. Brood some more. That's more my natural state.

Yet, I am good at making people smile. When I need to, I can put aside my personal trials to help a friend in distress. And that's a gift, I think. I love making others feel better. That's why, when I give readings, I read a lot of humorous poems. I enjoy the laughter.

Tonight, Saint Marty is thankful for the smiles in his life. They blow away the cobwebs, bring in fresh air.

Billy was marching with his hands on top of his head, and so were all the other Americans. Billy was bobbing up-and-down, up-and-down. Now he crashed into Roland Weary accidentally. "I beg your pardon," he said.

Weary's eyes were tearful, too. Weary was crying because of horrible pains in his feet. The hinged clogs were transforming his feet into blood puddings.

At each road intersection Billy's group was joined by more Americans with their hands on top of their haloed heads. Billy had smiles for them all. They were moving like water, downhill all the time, and they flowed at last to a main highway on a valley's floor. Through the valley flowed a Mississippi of humiliated Americans. Tens of thousands of Americans shuffled eastward, their hands clasped on top of their heads. They sighed and groaned.

What amazes me about this passage is that Billy Pilgrim is smiling the whole time. He's marching for miles and miles with his hands clasped on top of his head. When he bumps into Roland, he politely excuses himself, as if he's in the ticket line for a movie. And when he sees new people, Billy greets them with more smiles. I almost expect him to call out, "Welcome aboard!"

Perhaps Billy's smile is a byproduct of his time hopping. He has a larger vision. He knows what the past, present, and future hold. Or maybe it's just Billy's natural disposition. He's a friendly guy. For the most part, I'm known for being a pretty positive person, too. At work, I'm the life of the office. Always joking and laughing. Just the other day, a coworker said to me, "Can you just be here all the time? You make me so happy."

My good mood is a conscious choice. I have to work at it. If you've been reading this blog for any length of time, you already know that I have a penchant for dark moods and reflections. I am not a happy person most of the time. I worry. Fret. Brood. Dwell. Brood some more. That's more my natural state.

Yet, I am good at making people smile. When I need to, I can put aside my personal trials to help a friend in distress. And that's a gift, I think. I love making others feel better. That's why, when I give readings, I read a lot of humorous poems. I enjoy the laughter.

Tonight, Saint Marty is thankful for the smiles in his life. They blow away the cobwebs, bring in fresh air.

Tuesday, March 21, 2017

March 21: Crippled Man, Mongolian Idiot, Power of Language

The doorchimes rang. Billy got off the bed and looked down through a window at the front doorstep, to see if somebody important had come to call. There was a crippled man down there, as spastic in space as Billy Pilgrim was in time. Convulsions made the man dance flappingly all the time, made him change his expressions, too, as though he were trying to imitate various famous movie stars.

Another cripple was ringing a doorbell across the street. He was on crutches. He had only one leg. He was so jammed between his crutches that his shoulders hid his ears.

Billy knew what the cripples were up to. They were selling subscriptions to magazines that would never come. People subscribed to them because the salesmen were so pitiful. Billy had heard about this racket from a speaker at the Lions Club two weeks before--a man from the Better Business Bureau. The man said that anybody who saw cripples working a neighborhood for magazine subscriptions should call the police.

Billy looked down the street, saw a new Buick Riviera parked about half a block away. There was a man in it, and Billy assumed correctly that he was the man who had hired the cripples to do this thing. Billy went on weeping as he contemplated the cripples and their boss. His doorchimes clanged hellishly.

He closed his eyes and opened them again. He was still weeping, but he was back in Luxembourg again. He was marching with a lot of other prisoners. It was a winter wind that was bringing tears to his eyes.

I have to admit that, when Vonnegut starts using the terms "crippled" and "cripples," it makes me cringe. When Slaughterhouse Five first came out, however, those words were completely acceptable to use in polite conversation among people who knew nothing about living with physical challenges. Vonnegut isn't trying to shock or demean. He's just telling a story using the language of the time.

Of course, now, if an author described a character with a disability as a "cripple" (unironically and without attempting to capture some kind of social context), that author would most certainly be the target of justifiable criticism. Regardless of the current trend against political correctness, words can really harm and injure.

When I was in high school, I was in a world history class. The teacher--a nice man, full of progressive ideas--made a comment during a class discussion about a "mongolian idiot." I'm not even sure of the context of the conversation anymore. All I remember is being really shocked by his comment.

My older sister has Down Syndrome, and she was a student at the school. My mother had been fighting for my sister all my life. She fought to get my sister into a classroom. Fought principals and superintendents who didn't want to spend school funds to educate "retarded" children. Fought for other children with various disabilities. My mother was an activist for the rights of kids with mental and physical challenges.

So, when my history teacher talked about a "mongolian idiot," I took it very personally. It made me sad. It pissed me off. After class, I spoke to the instructor, told him how hurtful his language had been. He apologized to me, said that he never intended to offend. I accepted his apology.

Words can be very harmful. My mother taught me to speak against oppressive speech. Taught me to lift people up with my words.

Saint Marty is thankful for his mother's language lessons.

Another cripple was ringing a doorbell across the street. He was on crutches. He had only one leg. He was so jammed between his crutches that his shoulders hid his ears.

Billy knew what the cripples were up to. They were selling subscriptions to magazines that would never come. People subscribed to them because the salesmen were so pitiful. Billy had heard about this racket from a speaker at the Lions Club two weeks before--a man from the Better Business Bureau. The man said that anybody who saw cripples working a neighborhood for magazine subscriptions should call the police.

Billy looked down the street, saw a new Buick Riviera parked about half a block away. There was a man in it, and Billy assumed correctly that he was the man who had hired the cripples to do this thing. Billy went on weeping as he contemplated the cripples and their boss. His doorchimes clanged hellishly.

He closed his eyes and opened them again. He was still weeping, but he was back in Luxembourg again. He was marching with a lot of other prisoners. It was a winter wind that was bringing tears to his eyes.

I have to admit that, when Vonnegut starts using the terms "crippled" and "cripples," it makes me cringe. When Slaughterhouse Five first came out, however, those words were completely acceptable to use in polite conversation among people who knew nothing about living with physical challenges. Vonnegut isn't trying to shock or demean. He's just telling a story using the language of the time.

Of course, now, if an author described a character with a disability as a "cripple" (unironically and without attempting to capture some kind of social context), that author would most certainly be the target of justifiable criticism. Regardless of the current trend against political correctness, words can really harm and injure.

When I was in high school, I was in a world history class. The teacher--a nice man, full of progressive ideas--made a comment during a class discussion about a "mongolian idiot." I'm not even sure of the context of the conversation anymore. All I remember is being really shocked by his comment.

My older sister has Down Syndrome, and she was a student at the school. My mother had been fighting for my sister all my life. She fought to get my sister into a classroom. Fought principals and superintendents who didn't want to spend school funds to educate "retarded" children. Fought for other children with various disabilities. My mother was an activist for the rights of kids with mental and physical challenges.

So, when my history teacher talked about a "mongolian idiot," I took it very personally. It made me sad. It pissed me off. After class, I spoke to the instructor, told him how hurtful his language had been. He apologized to me, said that he never intended to offend. I accepted his apology.

Words can be very harmful. My mother taught me to speak against oppressive speech. Taught me to lift people up with my words.

Saint Marty is thankful for his mother's language lessons.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)